|

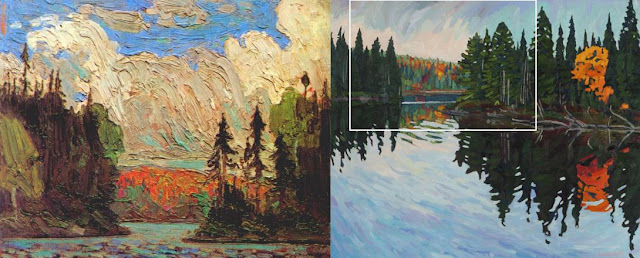

#2833 "The Sun of Whiskey Jack Bay"

36x38 inches oils on canvas |

The goal of this large canvas was to enhance the motion and perhaps the emotion of the scene. The virga falling from the top mixes with the light on the face of the distant clouds. Those brush strokes sweep into the outlines of the deciduous trees at the higher levels of the southern ridge, leading into the coniferous trees that line the shore of Whiskey Jack Bay. The white lines on the calm waters of the bay lead to the black spruces on the southern shore of the entrance to the bay. These trees lead both up and down. A path that sweeps downward leaps into the wave action of Canoe Lake and to the reflections of the black spruce on the western shore. The bright reflection of the soft maple should stop and hold your eye. Vertical lines lead to the source of the colour. The black spruce that surrounds the maple guides the eye back into the sky. The circle remains unbroken. That is what the sun can do to the nature of Whiskey Jack Bay.

|

| #1841 "October Bay" |

This was based on #1841 "October Bay", one of a series of about 50 paintings based on a paddle around Canoe Lake on Sunday, October 2nd, 2016. I was all by myself as the weather forecast of torrential rain was a bit scary. Luckily, I knew about deformation zones. I had the quiet waters of Canoe Lake all to myself.

I thought that #1841 "October Bay" deserved a larger format so that is what I did in #1888 "Whiskey Jack Bay". That 22x26 inch stretcher frame had been built by my father Nelson Chadwick (1924-2001) in the 1980s so it was and is a special piece of canvas for me. I am still using stretcher frames built by my Dad from the 6x6 inch post of the family home at 24 East Avenue in Brockville, Ontario. Waste not, want not.

I recognized the scene as one of the Tom Thomson weather records that I frequently include in my "Tom Thomson Was A Weatherman" presentation. Tom's record was of a cold frontal painting in autumn. The white box in the following graphic encloses the section of #1888 "Whiskey Jack Bay" that Tom painted.

As a result, this is a story of a journey and three paintings plus a fourth by perhaps Canada's greatest artist, the Canadian version of Vincent Van Gogh, Tom Thomson. They are all different as intended and by design. There are no rules in art and if there were, I would break them all... with intent.

When I posted this painting on my Fine Art America site, Artificial Intelligence generated the following text:

"Vibrant brushstrokes in red, blue, and green hues capture a shimmering river bordered by trees under a colourful sky. The vivid, autumnal colours suggest a lively, impressionistic take on a natural landscape, evoking a sense of both tranquillity and dynamism."

The words are an automatic, computer-contrived complement but sounded nice...

|

| Day 1 of "The Sun of Whiskey Jack Bay" |

This large studio painting was started at 10 am Wednesday, January 3rd, 2024. I have frozen my hands several times and the winter weather can keep me in the Singleton Studio - especially if the wind chill is significant. Over the intervening months, the canvas was loaded with layers of juicy oil. I was having fun. The design underwent several reinventions. A few people passed along suggestions. I listened as there was something to be said. I learn far more by paying attention than by talking. But in the end, there can only be one person holding the brush. Art is typically a solitary adventure anyway. Luckily, I paint for myself.

The canvas migrated back and forth from the display easel to the working easel conveniently positioned near the wood stove. I would apply oils wherever the inspiration mysteriously guided me until the canvas was all wet. At that point, the painting would shift back to display and further thought and deliberation. Five months of oil can really add up.

There comes a moment though when one must step away from the easel. That time arrived on D-Day, June 6th. My father along with an entire generation of Canadians fought for ideals and a way of life. "The Greatest Generation" phrase is certainly apt. Their sacrifices and efforts allowed the following generations to flourish.

|

| A cold low and very wet day sometime in May with "The Sun of Whiskey Jack Bay" |

Achieving creative mastery means making a thing and then trying to make a better one. We cherish the freedom to keep doing that until we die. That is a pretty good life thanks to "The Greatest Generation".

This approach to creative mastery applies both to art and the science of meteorology. Perfection will never be achieved in either and besides, perfection is nebulous, highly over-rated and only in the eyes of someone else. Mastery is a personal thing and should only be in the opinion of the creative. I would encourage never empowering anyone else with that judgment over your work... just my opinion of course.

There are twenty-eight paintings between January 3rd and today. Each was an opportunity to learn something - maybe even make a "better" piece of art, whatever you think that might be. For me, they are all steps in the creative journey and we have yet to find where that will go.

For this and much more art, click on Pixels or go straight to the Collections. Series links to the Canoe Lake Collection from October 1916. Here is the new Wet Paint 2024 Collection.

Warmest regards and keep your paddle in the water,

Phil Chadwick